By Vinesh Jha, ExtractAlpha CEO and founder

I recently gave a talk to the Master’s in Finance class at the University of Hong Kong on the topic of “quant quakes.” This is a topic near and dear to my heart, as it was, ultimately a quant quake which led to the founding of ExtractAlpha. And we’d just experienced another quant quake in the Chinese equities market.

The 2007 Quant Quake

Today, ExtractAlpha provides alternative data and stock selection signals to the world’s top systematic funds. We were founded in 2013, but the idea for the company dates back to 2007. At the time I had just started at Morgan Stanley’s largest prop trading desk, Process Driven Trading (PDT) after an earlier career in sell side and independent research and a brief stint in prop trading at Merrill Lynch. PDT had in some past quarters accounted for up to 25% of Morgan Stanley revenues, and had a long track record stretching back to 1993. But it was still a relatively small group, fewer than 30 people at the time of my joining.

That July, rumors were swirling around about some quant strategies not doing very well. And then, suddenly, on Tuesday, August 7, many quants, ourselves included, suffered large losses. (I’m not disclosing anything proprietary here; unfortunately, a version of these events was poorly documented in a WSJ article, and a subsequent book by the same author which I will not link to because it’s so inaccurate and so poorly written that it was my first exposure to the concept of Gell-Mann Amnesia). Some funds referred to the losses that day as “5 standard deviation events”.

On Wednesday, the losses at a lot of quant funds had extended, and had spread to Europe. By Thursday, things were even worse, and had spread to Asia, and it was now a “12 standard deviation event.” (Except it wasn’t, because quant strategy returns are not normally distributed). By that time, according to the WSJ, PDT had lost a half a billion dollars.

So, every fund in that situation is faced with a dilemma. Do you cut your book, because you may not live to trade another day? Do you hold on, in the belief that what you were witnessing was – had to be – a temporary dislocation? If you believed in your models, then at some point things had to snap back. The old saying (possibly apocryphally attributed to Keynes) is that “markets can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent” – or, in this case, that the particular market irrationality which you’ve been exploiting for a long time can pause or reverse for longer than you can retain AUM.

The nice thing about a prop trading group is that you only have one client – the bank in this case. Of course that client may decide that you need to pull your capital at any time. Hedge fund LPs, on the other hand, typically have at most monthly liquidity, so the hedge fund manager may choose to cut, or to hold on.

It turns out that holding on through that Friday would have gotten you back nearly all of your losses, if you were able to hold on! You’ve then got a positive “12 standard deviation” event on your hands (unless you’d included the prior three days in your variance estimates). And so if you held on, your monthly returns might have looked entirely unremarkable, despite some very remarkable intra-month moves.

Post mortem

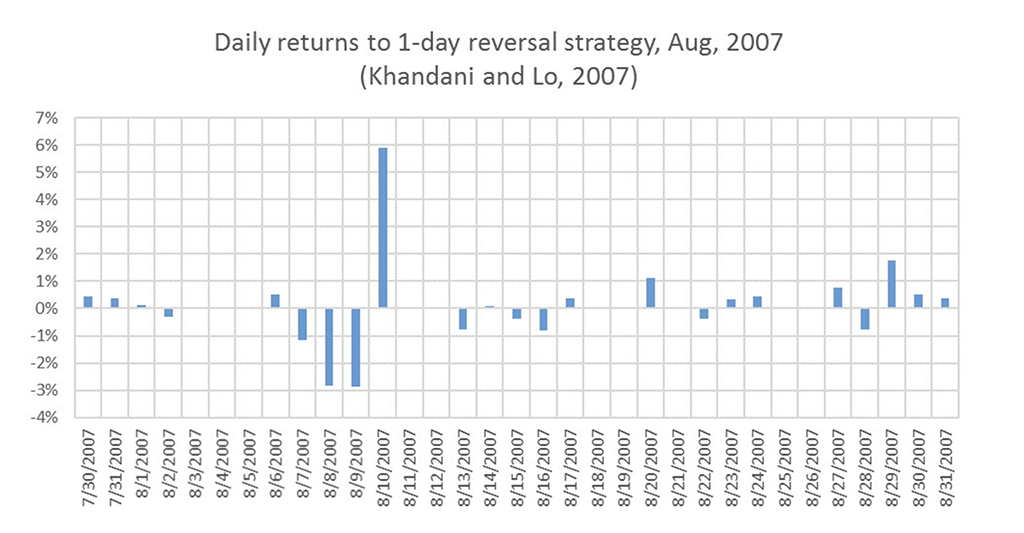

Here’s one chart which tells the story, in Khadani and Lo’s “What Happened to the Quants in August 2007”:

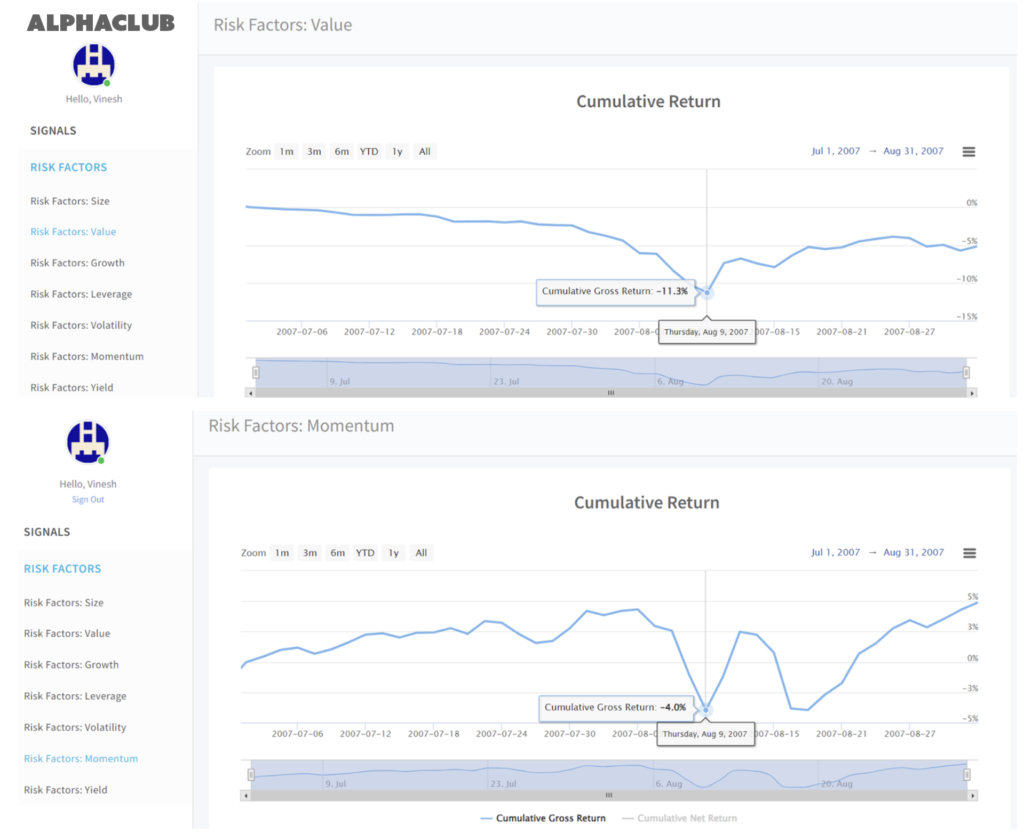

That chart uses a simple stat arb strategy, one-day price reversal. But you can observe similar return streams from long-short portfolios formed using basic quant signals like Value and Momentum; here are some charts from ExtractAlpha’s AlphaClub tool for that time period:

So that was the original 2007 Quant Quake. But how and why did it happen? The story which emerged was that Bear Stearns had recently shut down two of their MBS hedge funds, causing losses in the credit markets. What does that have to do with equity quant strategy losses? Apparently there was one multi-strat fund, with exposure to both credit and equity strategies, who had been affected by the credit losses. But credit books are illiquid, and so to cover their losses they unwound their (much more liquid) quant book. And then their quant book was very much like everyone else’s quant book, so their losses became everyone else’s losses, as they sold what everyone else was holding and covered what everyone else was short.

Why did all the books look similar? Because they all used similar inputs: the data that went into the strategies was largely the same (market data, financial statements, and the like); and the strategies built on top of these datasets were largely the same (reversal, Value, and the like).

So, a few lessons were learned. Even if your book is market-neutral (and, keep in mind, the markets in general were not directionally turbulent during that week), and even if you were neutral to the factors in your commercial risk model, you were still subject to strategy crowding risk. Your best bet is therefore to heavily diversify your alpha stream. This should increase your Sharpe ratio and capacity in normal times, and reduce your risk during liquidations. You can diversify your alpha stream by using different strategies on top of your standard data, but a really obvious way to do it is to look for novel datasets. Hence the idea for ExtractAlpha!

The China Quant Quake

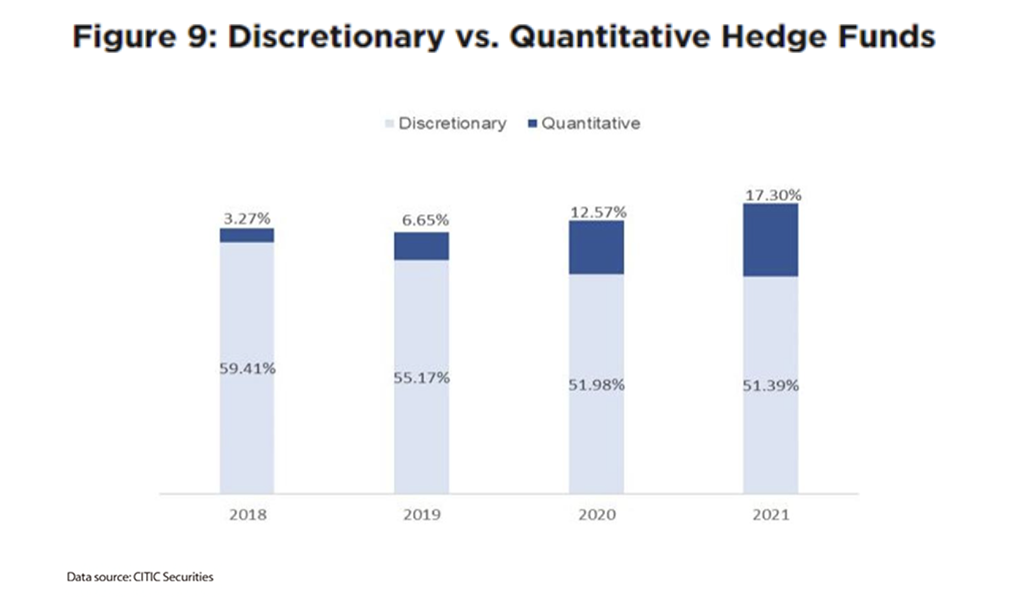

Fast forward to China in 2024. Quant strategies have been on the rise in mainland China in recent years, as these charts by Chris Zhang show:

But the chart talks about “quantitative hedge funds” in China even though hedging in the A-shares market is very imperfect. There are, for most investors, no single-name shorts (unless you can secure some from your PB’s inventory). So to build a hedge fund, you identify stocks with good alpha potential on the long side, and hedge with index futures. If you do this, it’s unlikely that your long book will look much like your short book in terms of risk exposures. This is especially true if one of the biggest factors you’re trading is SMB (small minus big), i.e., you’re long small caps and short a large-cap index. Now, SMB is not a factor that, even in 2007, most U.S. quant funds would have been trading. It’s a volatile factor and one which typically didn’t make the leap from academia to practice for that reason. But SMB was hugely popular among Chinese hedge funds going into 2024, as microcap names had massively outperformed the index in recent years.

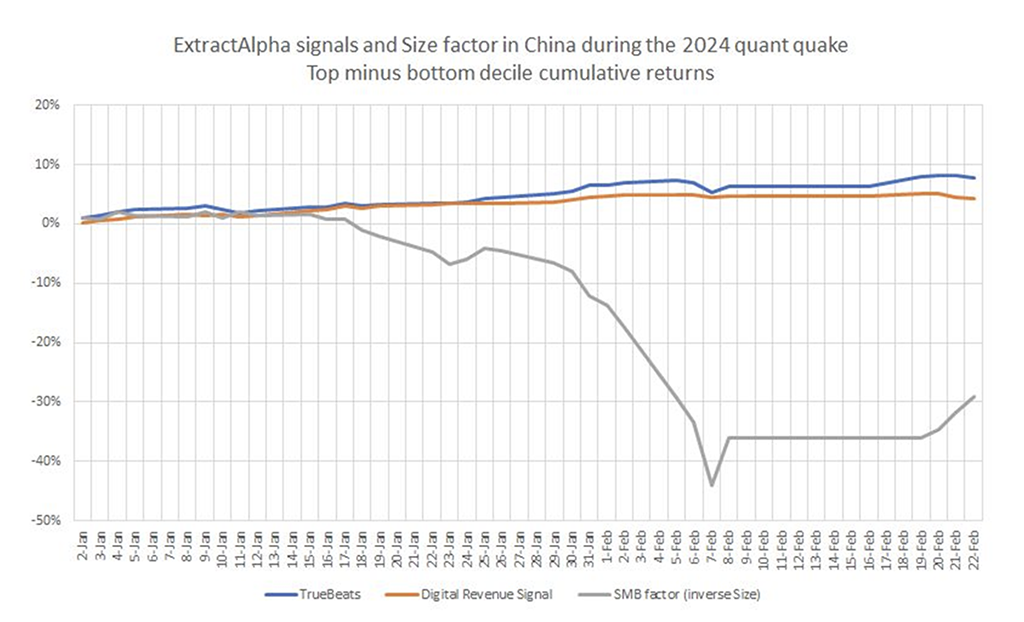

So, what happened next isn’t too much of a surprise given the stage I’ve set. Here’s a chart of fund performance which was making the rounds among institutional investors and quants in China in February:

This shows an event very much like August 2007. Note that many of the funds plotted here aren’t equity quant funds; this includes managed futures, CTAs which traded options, and other strategies as well.

Explaining the 2024 quake

But clearly there was some contagion effect going on. Why? Well, with the broad Chinese market experiencing declines, the Chinese government decided to deploy state funds, known as the “National Team,” to boost equity markets by massively buying index futures, starting on January 16. This buying caused, unsurprisingly, large losses on those index shorts held by the quant funds. The quants then quickly tried to unwind their long side, causing contagion on the long books which were concentrated in common factors like SMB. Subsequently many quants had trouble liquidating in an orderly way – for example, exchanges froze accounts, and brokerages blocked sell orders. Regulators, as they will, then blamed the quant funds for the turmoil which government intervention had caused in the first place.

This was just as much of a shock to the relatively nascent quant hedge fund world in China as it had been to U.S. hedge funds in 2007. Here’s a widely shared WeChat post (in Chinese) detailing one quant manager’s despair as his strategy turned south and he was unable to unwind. History doesn’t repeat, but it certainly rhymes a bit.

Takeaways

Running quant is really tough in China, and these events have made it even more difficult. Onshore quant funds tend to concentrate in a few, relatively simple, quant trades. There’s loads of unpredictable government intervention, which means that (a) market structure keeps changing and models are hard to calibrate; and (b) you may not be able to execute your strategy in an orderly way. Offshore quants had been looking to enter the A Shares market for several years, but many are giving up now and looking to other markets, which may benefit Japan or even India, where liquidity has deepened recently. And the government interventions, ultimately, actually served to decrease investor confidence in the market – for both domestic and international investors.

But there’s a silver lining to those bold enough to continue to run quant strategies in China: you don’t have to rely on simple quant trades! Employing the same lessons learned from the original quant quake, you can use alternative data signals to retrofit your portfolio for future quakes, diversify your alpha stream, and reduce liquidation and crowdedness risks. And yes, as it turns out, ExtractAlpha has some signals just like that! Our TrueBeats and Digital Revenue Signal products cover global markets including China A Shares, and use a diverse set of data inputs and features, such as detailed analyst forecasts, earnings management indicators, and web and social media data to consistently forecast earnings, revenues, and returns:

I hope this summary of two similar-but-different quant quakes was informative.

For more information on our datasets, visit our solutions page.